My research interest is physical activity and cancer survivorship. It’s personal for me. I was diagnosed with head and neck cancer more than 20 years ago and my prognosis wasn’t encouraging. I believe my recovery was improved because I was physically active before, during, and after treatment.

What is the Field of Cancer Rehabilitation?

Since 2000, oncology researchers have accumulated a mountain of indisputable evidence confirming the benefits of physical activity to cancer survivors:

- Increased effectiveness of treatment

- Reduced negative side-effects of treatment

- Lowered risk of recurrence

There are 15 million cancer survivors in the US, and each year another 1.7 million Americans are diagnosed with cancer1, which means it is very likely that this research directly affects you, or someone you know. We have done a great job of publicizing these benefits, but even so, about 60% of survivors are not active enough to experience these benefits.2 You, or someone you know, has likely accepted a life compromised by a functional impairment that developed as an untreated side effect of treatment. Functional limitations often contribute to depression, anxiety, and poor quality of life. This shouldn’t be.

Skilled MDs referred to as physiatrists, and therapists, working in the field of cancer rehabilitation medicine know how to help, but referral rates to cancer rehabilitation are as low as 2% – 9%.3 A constellation of barriers to referrals exists at the level of survivor, provider, system, payer, and policy.

Identifying and addressing the causes of this lack of rehabilitation services for survivors means asking and answering questions at the intersection of policy, standard of care oncology practice, and our fractured system of cancer rehabilitation care delivery that requires multiple visits to a range of specialists spanning different treatment disciplines.3, 4

Even straight-forward solutions are problematic. Tailored aerobic exercise is one of the most effective interventions to improve survivor status. Starting in 2013, in recognition of the importance of physical activity and in an effort to standardize cancer rehabilitation care, exercise guidelines were issued by the American Medical Association, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American College of Sports Medicine, the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, and the American Cancer Society.

The Crux of the Problem: The Conversation Isn’t Happening

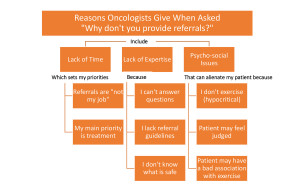

But here’s the rub: all these exercise guidelines recommend that oncology clinicians start the exercise conversation, evaluate a survivor’s needs, and make the referral. Not surprisingly, oncologists give some very good reasons why they are reluctant to offer exercise advice*:4,5

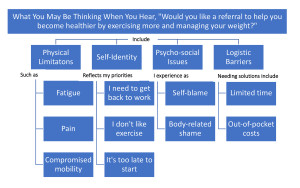

There are equally good reasons why cancer survivors tend to avoid the subject.*6

Meanwhile, left on the side-lines are the physiatrists and therapists of rehabilitation medicine who have the training but don’t have survivors. From their side, there are three reasons why survivors aren’t exercising.1,3

- The opportunity for a serious conversation between a physiatrist and a survivor about treatment impairments and the benefits of exercise rarely happens during oncology treatment.

- Neither oncology clinicians nor survivors know that most rehabilitation services for cancer survivors include exercise programming and instruction and are covered by insurance.

- As a consequence of the first two reasons, survivors often don’t ask for referrals to rehabilitation and frequently their oncologists don’t offer them.

So here we are, saddled with a system in which few survivors receive the help they need.

The Policy Environment: Opportunities for Change

The policy environment surrounding cancer survivors, cancer rehabilitation services, and the availability of community-based physical activity programs lacks coordination, direction, and enforcement mechanisms. In general it can be organized into three different arenas: medical organizations, legislative protections, and health equity advocacy.7

Leading the effort among medical organizations is the Institute of Medicine, whose series of reports on cancer survivors and their needs called for public commitments to support change. Its foundational 500-page report published in 2006, “From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition,” is often credited with prompting regulatory action by the American College of Surgeons (ACS). The ACS is the accrediting body for cancer healthcare providers, and in 2016 it mandated a timeline that linked accreditation to providing required services for cancer survivors including psychosocial support and survivorship care planning and rehabilitation services, now referred to as “survivorship care plans.”7 However, medical organization pressure only goes so far. Tellingly, the title of an October 2018 article published in the Journal of Cancer Education announced, “Most National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center websites do not provide survivors with information about cancer rehabilitation services.”8

The legislative acts that have been used to support cancer survivors are the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010. ADA addresses issues of employment, protecting cancer survivors whose treatment schedules or whose after-treatment limitations may require accommodation. The ACA addressed many insurance issues, but the act has been vulnerable to challenges since its implementation.7

Advocacy efforts addressing health equity have focused attention on populations who are less likely to have cancer rehabilitation services available: people living in rural communities, and minorities including American Indians, African-Americans, and Pacific Islanders.7

References:

*The images of oncologists’ and survivors’ attitudes were created by Nancy Litterman Howe.

1 Alfano, C., & Pergolotti, M. (2018). Next-generation cancer rehabilitation: A giant step forward for patient care. Rehabilitation Nursing, 43(4), 186-194.

2 Tsai, E., Robertson, M., Lyons, E., Swartz, M., & Basen-Engquist, K. (2018). Physical activity and exercise self-regulation in cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Psycho-Oncology, 27, 563-568.

3 Cheville, A., Mustian, K., Winters-Stone, K., Zucker, D., Gamble, G., & Alfano, C. (2017). Cancer rehabilitation: An overview of current need, delivery models, and levels of care. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 28, 1-17.

4 Pergolotti, M., Alfano, C., Cernich, A., Yabroff, B., Manning, P., Moor, J., . . . Mohile, S. (2020). A health services agenda to fully integrate cancer rehabilitation into oncology care. Manuscript submitted for publication.

5Smith-Turchyn, J., Richardson, J., Tozer, R., McNeely, M., & Thabane, L. (2016). Physical activity and breast cancer: A qualitative study on the barriers to and facilitators of exercise promotion from the perspective of health care professionals. Physiotherapy Canada, 68(4), 383-390.

6Blaney, J., Lowe-Strong, A., Rankin-Watt, J., Campbell, A., & Gracey, J. (2013). Cancer survivors’ exercise barriers, facilitators and preferences in the context of fatigue, quality of life, and physical activity participation: A questionnaire-survey. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 186-194.

7Silver, J., Stout, N., Fu, J., Pratt-Chapman, M., Haylock, P., & Sharma, R. (2018). The state of cancer rehabilitation in the United States. Journal of Cancer Rehabilitation, 1, 1-8.

8Silver, J., Raj, V., Fu, J., Wisotzky, E., Smith, S., Knowlton, S., & Silver, A. (2018, October). Most National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center websites do not provide survivors with information about cancer rehabilitation services. Journal of Cancer Education, 33(5), 947-953.

Stay posted Here

Stay posted Here

Nancy,

This blog is such an incredible, informative, relevant, and inspiring blog page. I am so happy to hear you are doing well! My dad was also diagnosed with head and neck cancer one month before I started the DNP program. (Squamous cell carcinoma, and he never smoked one cigarette or drank! Also, I have a degree in Exercise Physiology too, so I am really into this excellent blog! =). He is also doing superbly now! I have to tell you; I am 100% convinced that the coupling of a healthy diet and exercise is pertinent in cancer recovery and prevention of relapse!

An anonymous article called Combating Cancer with Tailored Workouts (2018) discusses how exercise can help to alleviate the physical symp¬toms of cancer and decrease the risk of depression and anxiety that often comes with a cancer diagnosis. Bluethmann, Sciamanna, Winkels, Sturgeon, and Schmitz (2018) agree that exercise is beneficial in decreasing many common cancer treatment symptoms during cancer treatments and after, as well as optimize cancer treatments in general. In my dad’s case, his post-cancer exercise routine was self-created and self-administered. There were no classes or instructions offered to him from his doctor or healthcare clinic. Thankfully, I already knew the great benefits of exercise for all people, including those affected by cancer, and had the exercise education. However, I was not educated on how to tailor a workout specifically to those recovering from cancer, and honestly, it frightened me. However, I knew we could figure out a safe way to regain his strength and flexibility and give him the confidence to go at it!

We did it, and now he is doing his workouts four times a week. He is currently 74 years old, and he told me last month that due to his diet and exercise changes after his cancer recovery, he feels better now that when he was 50! WOW!!!!!!! It’s so awesome.

One of your blog pictures showed some reasons why providers don’t talk about exercise with their patients. The article by Bluethmann et al. (2018) found that when exercise specialists worked with cancer patients on an exercise routine, as opposed to dieticians or providers, patients showed increased amounts of total physical activity. Correlating this information with one of the reasons listed in your blog that providers do not discuss exercise with their cancer patients is that they “can’t answer” patient questions about exercise and that they “don’t know what is safe.” I believe that education on proper exercise prescription for cancer patients is essential, at least to get them informed and started. Additionally, providers need to be ready and confident to refer patients to the proper and educated exercise specialists, which was another barrier listed as to why providers do not talk about exercise with their cancer patients. The provider does not, by any means, have to set up a three-month detailed work out plan. Bluethmann et al. (2018) tell us that influencing cancer patients across multiple levels may increase behavioral intervention effectiveness. Therefore, it’s crucial that providers begin the initial exercise introduction to their cancer patients. The research is outstanding at showing how beneficial exercise is for cancer patients, and this population needs to be educated about it and instructed correctly.

Reference

Anonymous. (2018). Combating Cancer with Tailored Workouts. USA Today, 146(2873), 4.

Bluethmann, S., Sciamanna, C., Winkels, R., Sturgeon, K., & Schmitz, K. (2018). Healthy Living After Cancer Treatment: Considerations for Clinical and Community Practice. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 12(3), 215-219.

Hi Kylee,

I thought I would just acknowledge that you and I have been “talking” off-line about your story of your partnership with your dad, and how terrific it is, and how I have invited you both to share your story (from both perspectives) with other survivors at a presentation on cancer rehabilitation that I am giving on April 22 at Cancer Support Community. cheers, Nancy

Nancy, thank you for your informative post. As a family nurse practitioner, I often support the referral for possible cancer diagnosis but am not active in the follow-up. I took for granted that the care was comprehensive and did not follow up with my patients on their lifestyle/well-being needs. I was also surprised by the data that oncology providers also struggle to convince or even have a conversation with their patients.

I have found that the role of the psychiatrist and rehab providers to be misunderstood. I feel they get pigeon-holed into thinking all they do is pain management with medication, but they offer so much more.

One area of support might come from a better understanding of the psychiatrist role. A meta-analysis study by Chiu et al. (2014) demonstrated the effects of mind-body interventions (MBI) on sleep in cancer patients, which they concluded improved overall health and wellbeing. Some of the interventions they looked at in the MBI were meditation, yoga, tai chi, and others. The authors noted there was low physical and emotional risk along with the low cost of implementing this type of intervention. They also stated that cancer patients widely received it but not commonly prescribed by providers due to providers’ bias.

I am encouraged by your drive and desire to reduce bias and increase knowledge of the importance of exercise and other modalities to improve the well-being of cancer survivors.

References

Chiu, H., Chiang, P., Miao, N., Lin, E., & Tsai, P. (2014). The effects of mind-body interventions on sleep in cancer patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(11), 1215-1223.

Hi Heather,

Your comment is the first time I’ve thought of psychiatric intervention in terms of cancer rehabilitation, but you are absolutely right. The rehab world often refers to “psychosocial support” but it is usually in terms of social workers and psychologists as counselors. One of the moderating factors in our breast cancer study in Edson College was sleep, which we assessed by asking patients to fill out a sleep diary. Now I wonder if we should have asked about whether or not the participant was receiving an intervention to increase the quality of her sleep over time. Thanks for bringing up that point.

Hello Nancy,

Thank you for such an amazing blog with great information for both providers and patients. I’m currently working as an Infusion Oncology Nurse. At my work, we have many different clinical trials for solid tumors and we treat many pancreatic patients. My patient population are mostly pancreatic cancer with various stages and many of them are stage IV. For pancreatic patients with no metastasis we would provide them chemotherapy/immunotherapy treatment prior or after surgery. At my work, our oncologists, nurse practitioners, and nurses always encourage patients to exercise while they are on treatment. Researchers have found that exercise could improve patient outcomes during adjuvant therapy (treatment after surgery) for pancreatic cancer (Cormie et al., 2014). Also, patients with stage IV pancreatic cancer are beneficial from exercise too. These patients usually receive intensive chemotherapy/immunotherapy treatment. However, exercise has shown to improve their quality of life. I have seen many patients who exercise have more energy to spend time with their family and happier. I really enjoy reading your blog, and I’m looking forward for more posts.

References

Cormie, P. F., Spry, N. U., Jasas, K. A., Johansson, M., Yusoff, I., Newton, R., & Galvão, D. (2014). Exercise as Medicine in the Management of Pancreatic Cancer: A Case Study. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 46(4), 664-670. DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000160

Reading about first-hand knowledge of the positive effects of physical activity for patients is always gratifying and inspiring. Most of the literature indicates that when patients receive encouragement to exercise, even as they are experiencing the effects of cancer-related fatigue, they report an improved quality of life. In my experience it is the nurses in the infusion rooms whose encouragement seems to matter the most. Your enthusiasm really makes a difference in helping survivors overcome the many barriers to physical activity during treatment. As a caring nurse, you improve lives on so many levels. Thank you.